Macbeth Centre - Its history

The Macbeth Centre - A history of its building

By Susanna Gretz

Origins

In 1875 and 1896 the two buildings we know as Macbeth Centre were first put up: not for adults, but for school children. You might well ask, what’s so special about that? Haven’t there always been state schools in London for primary children?

The answer is no, there haven’t. Free state schools have only existed since an act of Parliament, the 1870 Elementary Education Act, set up the London School Board. Before that, rich families paid for private schools and poorer ones paid (if they could) for church schools. For many children, there weren’t any schools at all.

When the School Board began building schools, not everyone approved. Free state schools for every child? An abomination, some people thought; it would mean the loss of poor children as a source of cheap labour! Many saw education not as everyone’s right, but as a privilege reserved for the very few. Nevertheless, the School Board had built enough London schools by 1900 to provide half a million school places. These were to be paid for by a combination of local rates and government funds - even though in reality, despite being intended for the poorest children, the new schools didn’t abolish all fees until 1918.

The 1870 Elementary Education Act, set up the London School Board

Waterloo Street School

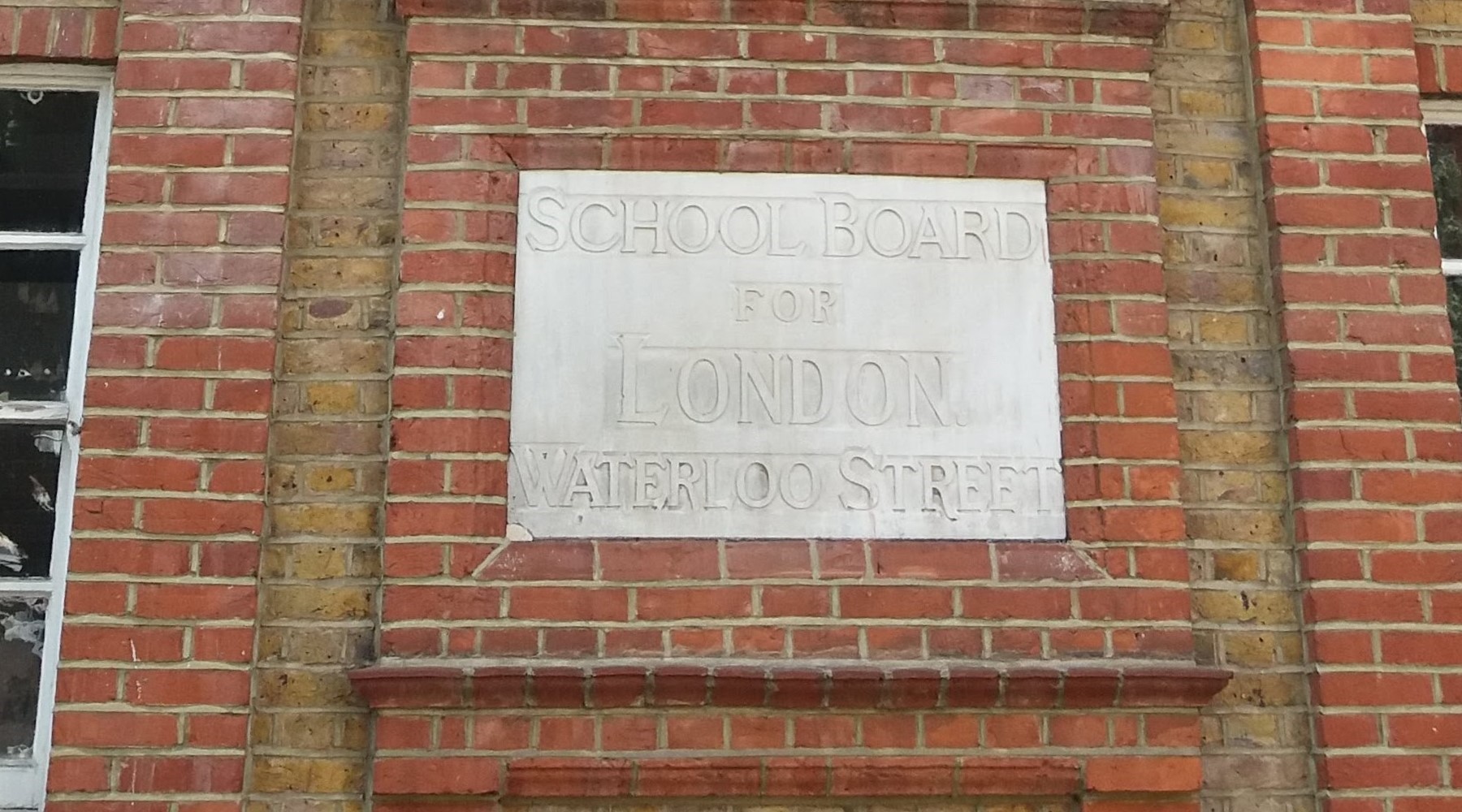

Located in what was once Waterloo Street, Macbeth Centre was originally the Waterloo Street School – one of the earliest “Board schools”. Today the 1875 building still bears its original name on the façade, just next to the street entrance. Schools like this one were typically sited in poor neighbourhoods, whose residents sometimes considered them an affront. Workmen building a new Board school in Clerkenwell had to have a police guard to protect them from the locals’ violence! For this reason, it was decided the new building should look as inconspicuous as possible. Perhaps this was why our earlier (1875) building was also given a very plain façade.

But who was its architect? This remains something of a mystery. Although plans for the later (1896) building, signed off by one Andrew Young, are available at the Metropolitan Archives, equivalent plans for the earlier structure are nowhere to be found there. According to the Archives staff, some of these may have been lost during World War II. However, the Archive files do at least list these earlier plans as having being signed off by ER Robson, the first architect hired by the School Board. During his years in the post (1871-84), Robson allegedly designed nearly 300 Board schools.

Today the 1875 building still bears its original name on the façade, just next to the street entrance.

Board School exteriors

Together with his partner, JJ Stevenson, and his chief draughtsman and successor, TJ Bailey, Robson is credited with replacing the Victorian gothic features and ecclesiastical spirit previously used for school architecture with the newer “Queen Anne Revival” style. Stevenson wrote of its “cleanness and brightness” and praised its “simple and homely” character. Bailey shared this view but vetoed an early move by the School Board to do without any decorative features. The Board President agreed, arguing that “if children were put into rough, unattractive or ugly places, they could not be expected to gain that admiration for beauty of form and colour which was necessary to human happiness”.

The wonderful double-curved brick “ogee” pattern on the rear façade of the 1896 annex

The name “Queen Anne” reflected the fact that the style borrowed elements of European architecture, including Flemish gables and terracotta “dressings”, like the wonderful double-curved brick “ogee” pattern on the rear façade of the 1896 annex. Robson felt that the Queen Anne style was “more enlightened and secular” than the Gothic – a preference shared by the Liberal or Progressive Party members who dominated the School Board. The Board’s tight budget ensured that brick, with white painted wooden sash windows, became the main building materials, in contrast to the more expensive (and more ecclesiastical in style) stone previously used for school exteriors. Britain had more extensive areas of brick clay than any other European country – and right here in Hammersmith & Fulham, there was a broad belt of brick earth that had been used since Tudor times. Its use for the Board schools also reflected the development, since the 17th Century, of improved brickmaking.

A foundation plaque was fixed to our 1875 façade, and featured a relief sculpture carved by the pre-Raphaelite sculptor Spencer Stanhope (1829-1908). Our plaque depicts two children receiving a book from a winged spirit.

Robson was very particular about the colours of the brick. He chose light yellow stock for the outside walls, while saving red terra cotta brick for borders and other decorative elements, such as carved panels of flower-like rosettes and other patterns to enliven the plain walls.

Bailey also added his mark to playground design, which included stone slabs projecting at intervals from the school façade. Instead of defacing the brick, the children were now encouraged to use these slabs for sharpening their slate pencils! The slabs do not seem to have survived, but stonework at the former “Boys’ Entrance” just inside the door to the café may have once been used in this way.

As was customary on many Board school exteriors, a foundation plaque was fixed to our 1875 façade, and featured a relief sculpture carved by the pre-Raphaelite sculptor Spencer Stanhope (1829-1908). Our plaque depicts two children receiving a book from a winged spirit. Other than his reference to the new schools as “sermons in brick”, such features were presumably as close as Robson wanted to come to religious symbolism. In his 1874 study, School Architecture, he wrote that “whether we like it or not, the education of the people is now governed by the lawyer, rather than the clergyman.”

Board School interiors

Robson and Bailey also gave the interiors of their new schools considerable thought; and despite changes over the years to the internal configuration of these spaces, some of their ideas are still visible at Macbeth.

Bailey insisted on “the most beautiful, easily washable glazed tiles or enamelled glazed bricks available”. Macbeth Centre still has some of these on the staircase walls. After doing research on schools in the U.S., Robson called for large assembly halls, as well as classrooms small enough to ensure the children could hear their teachers. He installed large, high windows, whose light could help protect children’s eyesight. In fact, the ropes and poles used in some of Macbeth’s classroom windows may well be replicas of the original fittings.

Robson also maintained that high ceilings were needed to ensure better ventilation in classrooms housing the many - often smelly - pupils! He made sure that – unlike most previous school designs – there were ample cloakrooms for the girls, washbasins, toilets with doors (!)– and adequate heating.

Robson and Bailey were almost unique in their concern for both educational and architectural aspects of school design – in short, they were true educational reformers. Their supporters included Arthur Conan Doyle, who eloquently conveyed his own view through the voice of Sherlock Holmes in the story “The Naval Treaty”. As they look through a train window at the roofs of one of the new schools, Holmes assures Watson that these are “Lighthouses, my boy! Beacons of the future! Capsules, with hundreds of bright little seeds in each, out of which will spring the wiser, better England of the wiser, better England of the future.”

Early Years

The 1875 Waterloo Street School was built on the premises of a former Wesleyan Methodist chapel, and was officially opened in January 1876.

Huge population increases in Hammersmith meant that new schools like this one became ever more crowded. Robson’s response included the compulsory purchase of several terraced houses in what is now Down Place; later, he organised the purchase of terraced houses in Waterloo Street, to make room in 1896 for his design for the somewhat more ornate annex across the playground.

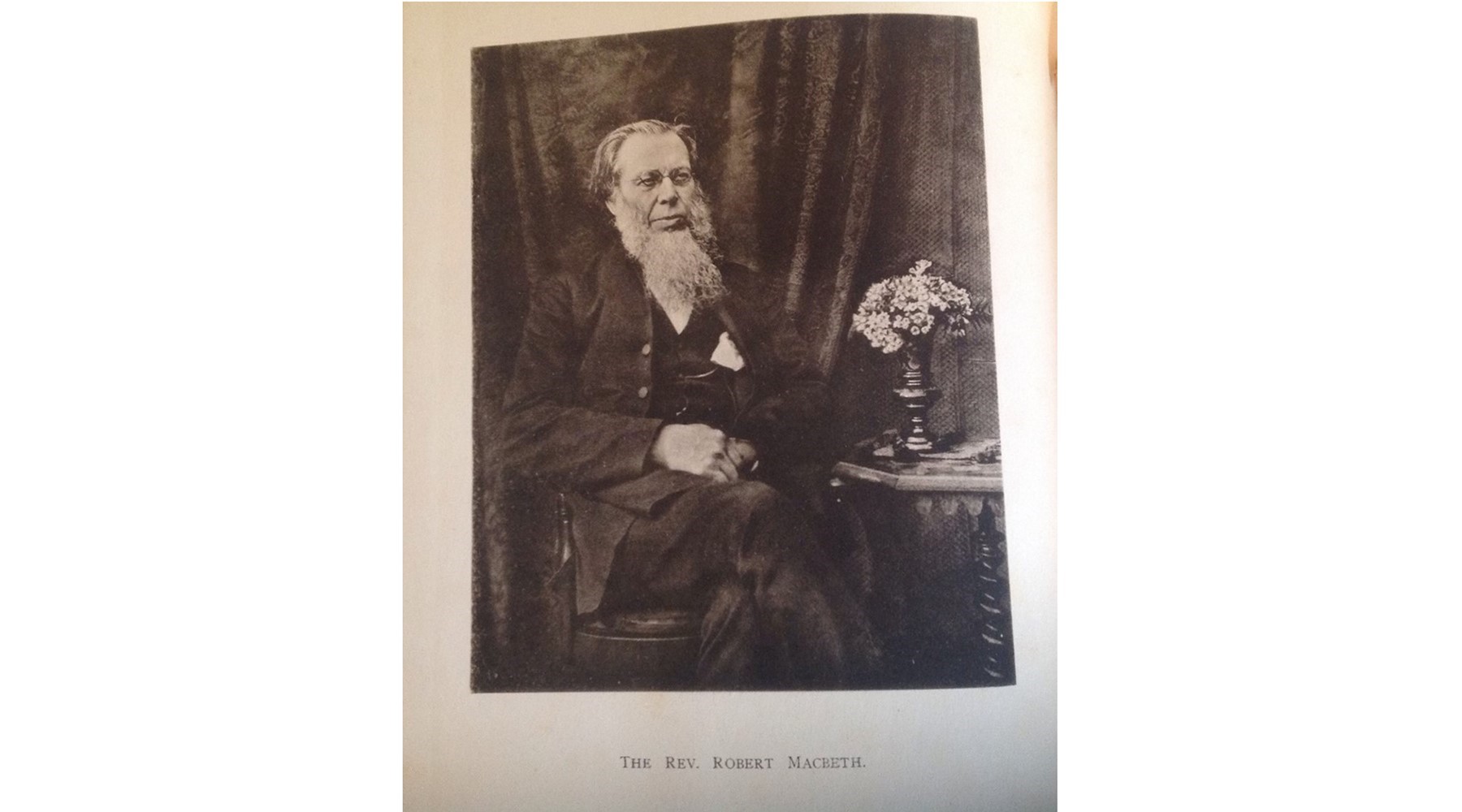

The Rev Robert Macbeth - Macbeth’s staunch support of secular education involved many local initiatives, including the establishment of the Hammersmith Central Library in 1905.

During the early years, one of the school’s Waterloo Street neighbours was Robert Macbeth, minister of the Hammersmith Congregational Church. Macbeth’s staunch support of secular education involved many local initiatives, including the establishment of the Hammersmith Central Library in 1905. In 1937 after Macbeth’s death, the street was renamed in his honour.

The school was damaged, but luckily not destroyed, by the 1940 bombing in World War II. In 1944, St. John’s C of E School was relocated to the Waterloo Street School. After the war the school reopened, but a now falling population in inner London meant it finally closed in 1983. It then stood empty for many years.

Recent years

In 1991 the buildings were finally reopened by the Inner London Education Authority as the Borough’s new hub for adult education: Macbeth Centre. The plaque commemorating this event hangs just inside the front door to the 1875 building.

Local newspaper article of the official opening of the Community Education Centre in October 1991.

As the years go by, some Board schools have been luckier than others. Many have been replaced with more modern schools such as the Bonner Street School in Hackney, once considered a fine example of Robson’s early designs. In Bigland Street, Shadwell, the former Chapman Street School - another early Robson design - was rescued from demolition at the eleventh hour in 2010, given Grade II Listing by Historic England – and is now the Darul Ummah Community Centre. Its façade still bears a relief sculpture by Spencer Stanhope, this one representing “Knowledge strangling Ignorance”. In Clerkenwell, Robson’s Bowling Green Lane School houses the practice of Zaha Hadid, its familiar “high, plain, light rooms” (J. Meades), now occupied by her young architects.

In nearby Becklow Road, Hammersmith, is the former Victoria Road Junior School, built by Robson in 1875 and featuring a Stanhope cartouche identical to our own: two children receiving a book from a winged spirit. The school has been transferred to a modern building nearby, while the original building was converted in 1995 into flats for the Shepherds Bush Housing Association. Unlike Macbeth, the Becklow Road building was given Grade II listing in 1984. However, the exterior of Macbeth Centre looks in decidedly better shape – the reason presumably being the fact that Macbeth – under the jurisdiction of LBHF – is obliged to abide by an official covenant requiring it to be used solely for educational purposes.

Macbeth Centre today

These days we can’t assume that the Macbeth buildings inspire the same “admiration for beauty of form and colour” hoped for so long ago by the London School Board. However, according to more recent commentators (A. Saint and J. Holyoak in the journal The Victorian, 2007), the early Robson schools were “often among the more charming”, adding that these distinctive buildings – or at least, the few which remain – form “part of the identity…of the whole city”. The buildings of Macbeth Centre, we hope, will long continue to play a local part in that identity.